This essay appeared in the Chicago Tribune on February 26, 2020. Since then, the rule requiring hunting images in the duck stamp has been rescinded.

By Kerry Luft

One of the greatest conservation programs in U.S. history unquestionably is the federal duck stamp, which is worthless for postage but invaluable for migratory birds, other wildlife and people. Since its inception in 1934, the program has financed the creation or protection of 6 million acres of habitat for migratory waterfowl and other wildlife, including the establishment or expansion of more than 300 national wildlife refuges — at least one in most states.

It’s also one of the most efficient government programs imaginable. By law, 98 cents of every dollar spent on duck stamps must go directly toward habitat within the national refuge system, which belongs to and benefits all Americans. These lands do far more than provide food and habitat for birds and other wildlife. Wetlands in particular are beneficial to people because they ease flooding and filter the water that flows through them, yet they are disappearing at an alarming rate.

The vast majority of duck stamp dollars come from waterfowl hunters, who must purchase the $25 stamps each year before they can legally hunt ducks and geese. The program is one of the many examples of how hunters drive conservation in this country.

So why do I — a passionate waterfowl hunter who spends many days in marshes each fall — strongly oppose a proposed rule change by the Department of the Interior that would mandate hunting-related themes to be portrayed on the duck stamp? Simple: It’s a terrible idea.

My reasons are in part driven by economics. The rest is plain common sense.

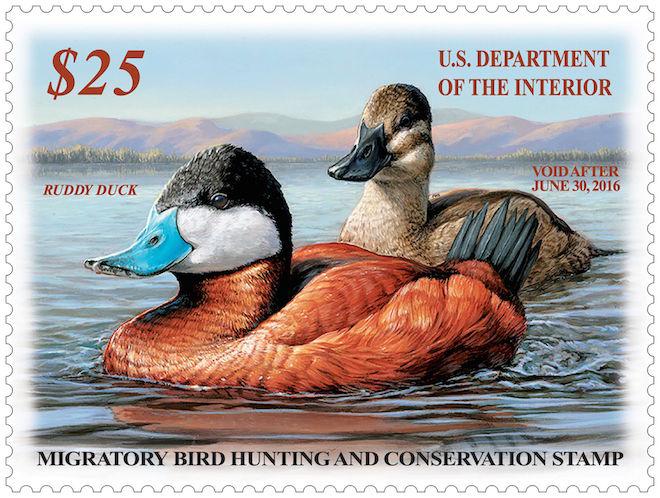

Duck stamp images are chosen annually in a national contest in which artists paint one of five designated species of waterfowl. While hunting themes now are optional, the proposed rule change would require artists to include “one or more waterfowl hunting specific elements or a waterfowl hunting scene as part of the design.” That might include a decoy, a Labrador retriever bringing back a goose, or a camo-clad parent and child. The proposal is the byproduct of a well-intended plan to support hunting and its role in conservation, and the appeal to hunters is undeniable.

Yet even the most dedicated hunters must admit that our numbers are dwindling. Statistics from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service suggest that there are about 1.1 million waterfowl hunters in this country, about half of what we had 50 years ago. As current hunters age, more people embrace urban lifestyles and access to good hunting opportunities dwindles, that number is likely to drop further.

Though annual duck stamp sales exceed the number of waterfowl hunters — around 1.5 million are sold each year, generating more than $36 million for habitat — hunters obviously buy the bulk of them. Many hunters buy more than one, sometimes because they lose one but more likely because they recognize the program’s value.

If hunter numbers continue to decline, so too will the funds that are so badly needed to conserve habitat. That will affect not just duck hunters but all of us: bird watchers, wildlife photographers, other visitors to the refuge system and most important, those of us who care about flood mitigation and clean water.

It makes little sense to exclude or possibly alienate those people whose idea of a good time doesn’t include wading through muck and mire in the predawn hours in hopes of bringing home a duck dinner, not to mention those who actually oppose hunting. We hunters will buy the stamps regardless; we need to encourage others to buy them too.

A far better choice would be to expand the pool of potential buyers of the duck stamp, perhaps by requiring any adult who wishes to enter a national wildlife refuge for whatever reason to purchase one. After all, the duck stamp makes these refuges possible, and while the stamp’s price is modest, its impact is not.

I would embrace such a rule change. The current proposal, now in the public comment stage of implementation, should be rejected.

Meantime, if you care about birds, other wildlife and the benefits of wetlands, buy a duck stamp or two — even if you have no intention of hunting. It’s the most economically efficient thing you can do for conservation.

Kerry Luft is the executive vice president of the Max McGraw Wildlife Foundation.